Modern Slavery in the UAE: Prevalence, Power, and the Limits of Reform

12/24/20253 min read

The United Arab Emirates occupies a contradictory position in global assessments of modern slavery. According to the 2023 Global Slavery Index, the UAE has the second-highest prevalence of modern slavery in the Arab States region and ranks seventh worldwide. At the same time, it is often cited as one of the countries in the region taking the “most action” to address the problem. This paradox highlights a central reality: reforms exist, but structural exploitation persists.

Scale and Prevalence

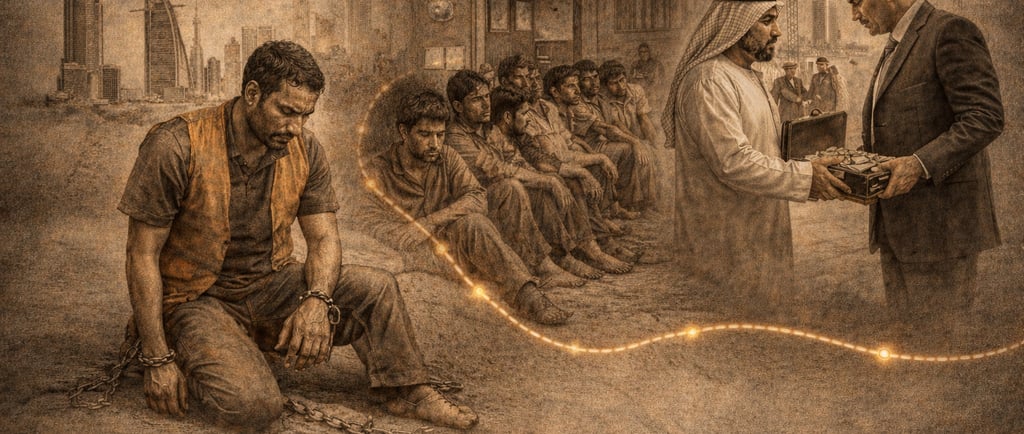

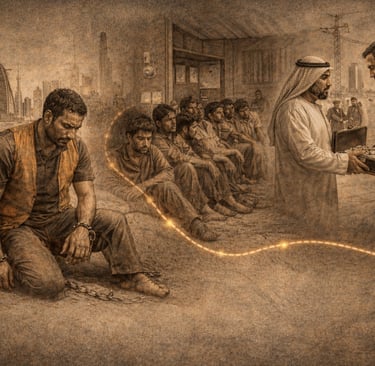

An estimated 132,000 people were living in conditions of modern slavery in the UAE on any given day in 2021. This equates to 13.4 people per 1,000 residents, a rate among the highest globally. The overwhelming majority of those affected are migrant workers, who make up roughly eight million people—nearly the entire workforce—drawn largely from Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Middle East.

Their vulnerability is closely tied to the kafala (sponsorship) system, a legal framework that historically granted employers extensive control over workers’ residency, employment, and ability to leave the country.

Kafala and Forced Labour

Although the UAE has announced reforms intended to weaken kafala, the system’s core power imbalance remains largely intact. Migrant workers who leave abusive jobs risk being reported for “absconding,” losing legal status, or facing detention and deportation. Employers continue to wield control through threats tied to visas, housing, and wages.

Forced labour has been documented across sectors, particularly in construction, domestic work, and services. During preparations for Expo 2020 Dubai, workers from countries including Bangladesh, India, Kenya, Nepal, and Pakistan reported passport confiscation, unpaid wages, excessive working hours, and substandard living conditions. Similar patterns persist in domestic work, where migrant women often work without rest, for minimal pay, and with little legal protection.

Despite extensive documentation, in 2021 the UAE officially identified only one person as a victim of forced labour, with no further details released. In practice, allegations of forced labour are frequently treated as regulatory or contractual violations rather than serious criminal offences.

Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking

The UAE is also a destination for forced commercial sexual exploitation, affecting women and children from Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa, and parts of Asia. Although the government does not publish comprehensive statistics, court data indicates that the majority of trafficking convictions in 2021 were related to sexual exploitation.

Trafficking patterns often involve deception: women are promised legitimate work—such as domestic service, massage therapy, or modelling—only to be forced into sex work upon arrival. In one documented case, traffickers forged a passport for a teenage girl, forced her into domestic labour, and then into commercial sexual exploitation. Similar cases have been recorded involving Thai nationals recruited under false pretences.

Forced Marriage and Gendered Vulnerability

Women’s vulnerability to modern slavery in the UAE is compounded by gender inequality embedded in law and practice. Forced and child marriage remain areas of concern. While national prevalence data is unavailable, international records show cases involving foreign nationals forced into marriage in the UAE, even during periods of global travel restriction.

For Emirati women, male guardianship laws continue to enable coercion in marriage, with limited legal avenues to annul forced unions. There is no explicit provision allowing women to dissolve a forced marriage solely on the basis of coercion.

COVID-19 and Heightened Risk

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased vulnerability. Wage reductions were legally permitted, recruitment debt deepened, and many migrant workers were repatriated without receiving owed wages. Crowded labour accommodations further exposed workers to health risks, while movement restrictions limited access to assistance.

Government Response: Progress and Limits

The UAE has invested heavily in anti-trafficking frameworks, including the establishment of the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking (NCCHT) and annual reporting. It operates trafficking hotlines, conducts public awareness campaigns, and provides training to frontline responders—placing it ahead of many regional peers.

However, these efforts remain uneven. Support services are largely limited to female survivors of sexual exploitation, while men and victims of forced labour without a trafficking designation often receive no assistance. Forced marriage is not fully criminalised, and key exceptions undermine protections around the legal age of marriage.

Critically, the UAE has not taken meaningful steps to eradicate modern slavery from government or business supply chains, despite having significant economic capacity to do so.

Structural Challenges

Recent labour reforms prohibit recruitment fees and allow job changes without employer permission, yet enforcement remains weak. Workers continue to incur high recruitment debts, face employment bans if contracts are terminated early, and receive little protection against wage theft or passport confiscation. Domestic workers, despite a new law introduced in 2022, remain excluded from core protections such as a minimum wage.

Conclusion

The UAE’s modern slavery problem is not rooted in the absence of laws, but in selective enforcement and structural inequality. Migrant workers remain legally and economically dependent, women face compounded vulnerabilities, and exploitation is often reclassified as administrative misconduct rather than treated as a serious crime.

Until the kafala system is fully dismantled, forced marriage criminalised without exception, absconding laws abolished, and supply chains brought under binding human rights scrutiny, modern slavery will remain embedded in the UAE’s economy—managed, not eradicated.